In my last blog post I mentioned feeling like an artist working hermetically in my space. The idea of the artist working in a space in solitary is very romantic. If conversations with people at art shows and sales and even when I am out and about town are proof enough, the average person seems to think of an artist sitting alone in a zen like experience, joyously skipping between painting surfaces, elated to be doing something fun for a living; but tortured at the same time, suffering to find something to eat, irreversibly poor.

As I was reading an article on “Walden, Revisited” at the DeCordova, I started to feel more conflicted by the idea of hermeticism. When I think of hermeticism, I think of an old man who lived down the road from my Uncle Roger. I seem to remember that occasionally my cousin Chris and I would venture down and talk to the man, who had crudely constructed his little ramshackle shack out of mismatching woods. He was grizzled and I have no idea what he talked about. He is just a vague image in my mind. Conversely, I think of Strickland in Maugham’s “The Moon and Sixpence.” He is so taken by his painting that he is unaware of love, social niceties, or even the state of his own body; he was dying of leprosy but still painted on.

The show features “Two Cabins,” by James Benning; comparison between Thoreau’s cabin on Walden and the unabomber, Ted Kacynski’s shack in Montana. The strange correlation between utopia and dystopia becomes evident. They are both other worlds which we are in one case yearning for an in another case heading toward. Perhaps neither is entirely attainable or perhaps both are ultimately truisms dependent on the other. Maybe it is the job of the hermetic artist, one who is detached from society if only in perception, to reveal the utopia within our more dystopian reality. Utopia only exists in that we know what does not work. We have forever been trying to produce machinery and goods which will make life easier. It is a utopian ideal that life should be easier, but as we grow to find our lives easier, we realize that error of our leisure. Our leisure begets idleness which as a byproduct results in a dystopian society.

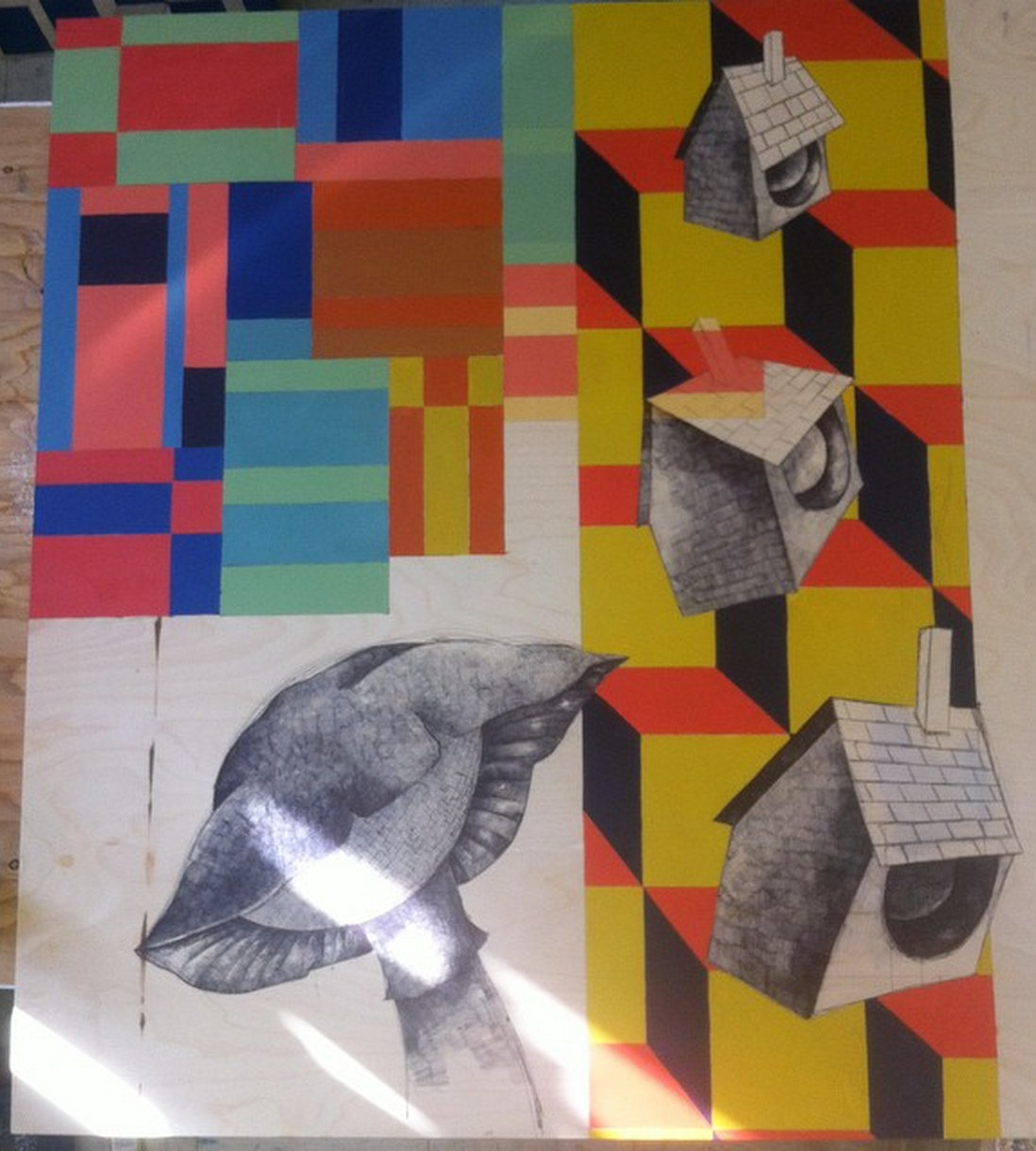

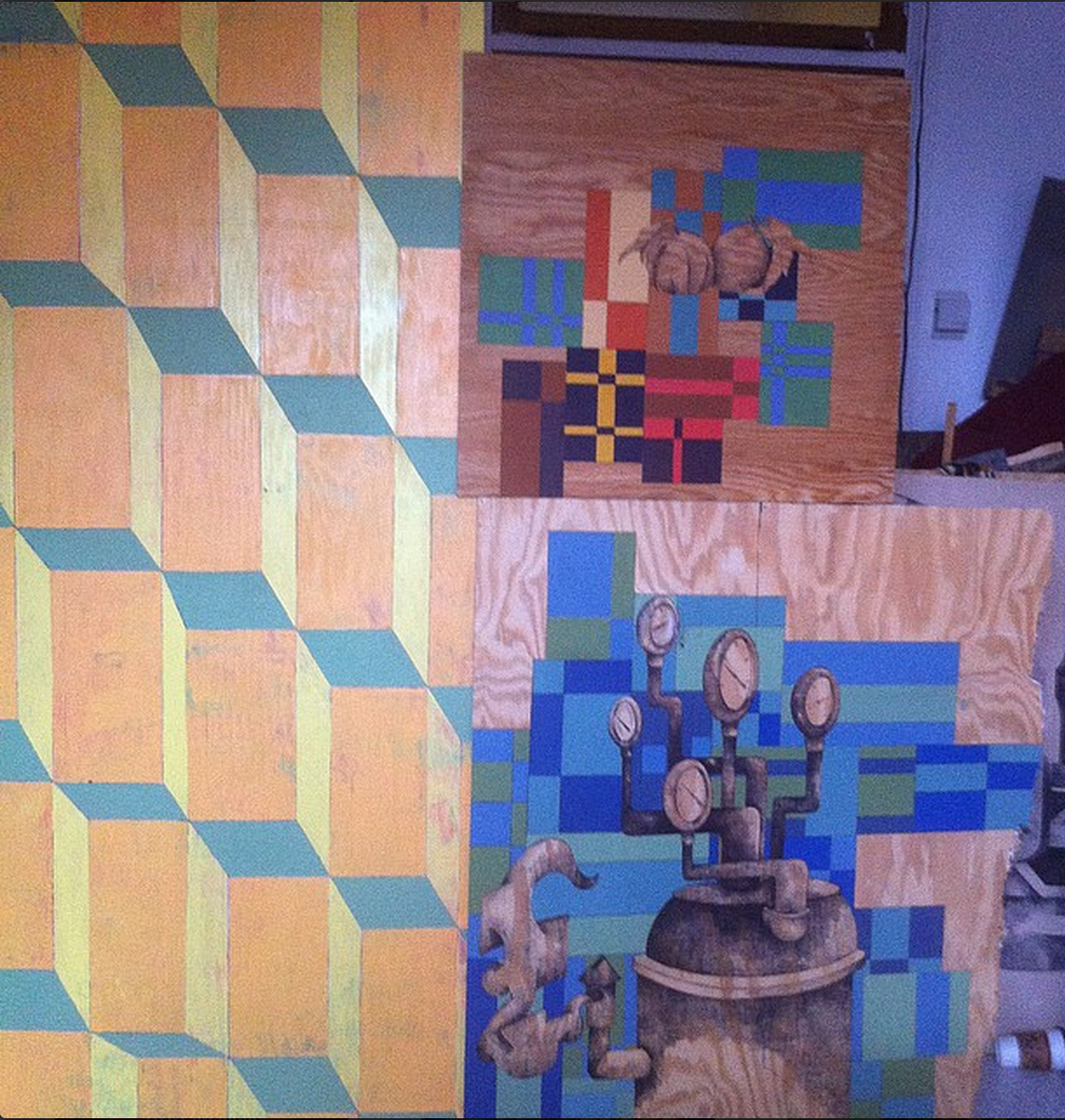

As I sit in studio visiting and revisiting mathematical patterns and optical illusions coupled with drawings of nature and the failures of our industrial society, I begin to see the paradoxical relationship of Utopia and Dystopia. The work begins to make more sense. It is more simply put an accumulation of the things we want and the things we wanted and their propensity to change in relation to what we have.

My desires are mercurial at best. I have started reading “The Sea Wolf,” by Jack London. Humphrey Van Weyden is a learned man from San Francisco who is lost at sea after his Ferry boat is struck and sinks. He is picked up by a sealing schooner set for the Japanese coast. At the helm of this ship is Wolf Larsen. The two characters talk of their varying ideals of life; Larsen is a scourge and an autodidact, Van Weyden a studious scholar. Larsen yearns for adventure and the knowledge within that adventure, but only insofar as it will benefit him economically. Van Weyden is wound up in his philosophical ideals of life. He is very detached from what life actually is. He grows to value his own breath, as he could surely have been left for dead at any moment thus far in the book. And so I find the conundrum that always stings my being and my creativity. Adventure is dangerous by necessity. Without any threat to our well being there is no adventure. We must overcome threats in order to feel that rush indicative of an adventure. That rush coupled with the bucolic or the mathematical precision of a city’s architecture yield a sense of accomplishment and Benjamin’s aura. I yearn for both settings. I yearn for the danger and I yearn for my work. I am at once Van Weyden and Wolf Larsen. I am Nick Carraway on his ledge in New York city, experiencing life both within myself and witnessing myself.

Peace

-Mike